Jesus came from Galilee to the Jordan to be baptized by John. But John tried to deter him, saying, “I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?” Jesus replied, “Now, let it be so; it is proper for us to do this to fulfill all righteousness.” Then John consented. As soon as Jesus was baptized, he went up out of the water. At that moment heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him. And a voice from heaven said, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.” Matthew 3:13-17

The Baptism of Jesus

This week the Christian Calendar used by the Church around the world brings us to the celebration of Jesus’ baptism. We began in Advent with the promises that the Anointed One – that God’s Son – would come into the world, we celebrate that first coming at Christmas, and then last week, with Epiphany we celebrated God’s revealing of himself not just to the Jewish nation, but to the world.

Now, today, we fast forward some 30 years to the start of Our Lord’s public ministry, where he’s revealed not just to prophets and scholars, to his parents and shepherds, but is revealed publicly to all who were there to hear “This is my beloved Son” echoing through the clouds.

And, of course, it’s a significant day for us, too. After all, baptism is our entry into the Body of Christ; it’s the sacrament that sets us apart and identifies us as Christians – together with a life that cooperates with the Holy Spirit to live a Christ-like life, asking for forgiveness when we mess up.

But, if we stop to think about it, the baptism of Jesus raises some questions.

Baptism for Repentance of Sin

John the Baptist, Jesus’ cousin on Mary’s side, was a very strange man by any account. He lived in the desert wearing a cloak of camel skin and eating only grasshoppers and wild honey: I’m thinking he’s the kind of guy who turned heads and probably left a bit of a stench when he walked by.

Now, he started his ministry a couple years before Jesus, announcing that he was preparing the way for the Lord, the Anointed One of God. And, with that, he called people to confess their sins and to be baptized – to be washed – in the waters of the Jordan River.

And, the bulk of his message as recorded in Matthew’s Gospel is that it simply isn’t enough to claim to belong to God’s family without living a life that is in accordance with God’s will.

So, one day, Jesus comes to be baptized.

But wait a second. Jesus is the Son of God. Jesus, scripture assures us, is like us in every way except for sin. If there’s one person ever who didn’t need baptism, wouldn’t that be Jesus? In our Gospel lesson today, even John the Baptist is confused: it says, “John tried to deter him, saying, ‘No, it is I who need to be baptized by you; why are you coming to me?”

To find the answer, I want to suggest that maybe there’s more to baptism than meets the eye.

Saving through water: not just a New Testament idea.

You see, if we study the whole story of God’s salvation as one continuous action, rather than picking and choosing what we read, we find that this isn’t the first time God uses water to save his people.

As we said last week, our God is in the business of revealing himself those who seek him – that’s something he’s done throughout history, and it’s something he wants to use you and me to do even today. (Which reminds me: how have you done being an Epiphany, a revelation of God to someone who is searching this past week?)

But, together with God showing himself to those who seek him, from the beginning, he’s in the business of offering himself to be in relationship with his creation. He does that, we’re told, in covenants – in promises made – in which the Almighty God of heaven and earth offers us his boundless blessing and mercy in exchange for our recognition that he is Lord; in exchange for our trust and loyalty, but more importantly, our acknowledgement that when we don’t trust him, when we forget that he’s Lord, we’re in the wrong, and we need to ask for forgiveness.

We see this even from the very beginning.

On the very first page of our Bibles, in just the second sentence, we see God the Holy Spirit working through water. God, wanting to make a creature in his Image, a creature capable of true love and sacrifice, a creature capable of choosing good over selfishness, created a home for us, a home – even the most worldly of scientists would tell us – is special, not because of rock, or an atmosphere, but because it has been shaped by the water that sustains life as we know it.

From the beginning, God is at work, “the Spirit of God hovering over the waters”, to create a home for us to live in relationship with Him. And, from the beginning, he reveals himself to those first people, and offers himself to them, reaches out to them, inviting them into a covenant: ‘you can live in this paradise if you trust me as God, and you’ll show your trust by not touching that one tree – the rest is yours.’

Of course, we know how that chapter ends: we’re not happy with the 99.9% we were given, but broke that one simple rule, even though we knew that choosing to live apart from God would cost us dearly.

Time goes on, as some choose to live for the one true God who revealed himself in creation, while most others choose to live for themselves. Then, God reveals himself and offers himself in relationship to us in a man called Noah, and his family.

Humanity, we’re told, had become murderous, obsessed with killing for power. God offers himself to Noah, and tells him, and his sons, and their wives to be fruitful and multiply and fill the land, on the condition that they remember that each life is made in God’s image, and therefore no person should kill another.[1]

And how did God enact that covenant? How did God offer salvation to Noah, and bring he and his family to their promised land? He saved them through water; mighty waters of death that destroyed all in their path – except, for those whom God had called and carried through, those same waters became a fresh start, a new life, a new chance to live according to God’s will.

Time goes on, thousands of years pass, and God has chosen Abraham and his descendants to be the chosen people through whom he will reveal himself to the world. This chosen family find themselves in Egypt where, over generations, they become enslaved.

Again, God reveals himself – this time to Moses – and God offers himself to be in relationship with them; offering freedom and blessing and mercy in exchange for their trust and loyalty. The people set off on their journey of trusting God, and find themselves trapped, with the sea on one side and an angry army on the other. And, once again, God uses water to save his people: his chosen people are those who walked through the sea on dry land, while the army is drowned as the tide washes over them.

Of course, we know how this chapter goes – those chosen people saved from slavery were particularly bad at keeping the “trust and loyalty” part of their covenant. In the desert they were afraid that they would starve, even though God provided food and water for them, and then they had the gall to complain about the food they were given!

God promised them a land overflowing with crops and cattle and milk and honey, but they hadn’t trusted; after 40 years, God raised up Joshua to take Moses’ place and lead his people to the promised land. But there was a problem; the river – the Jordan River – was in their way.

This, we read in Joshua 3[2] was an opportunity: an opportunity for God’s people to consecrate themselves, to make a fresh start in choosing to live according to God’s will for their lives, to live as his chosen people. And, once again, God is saving his people through water. They consecrate themselves in accordance with the Law, the priests enter into the flowing water and stand there, as the water dries up as everyone – toddlers, old men and old ladies – crosses the river without harm, arriving in the promised land.

Our own Baptism

God works through water. And, in Jesus, we’re all invited into those waters of baptism.

But, what is offered is no mere bath, nor a simple “symbol” for a fresh start, nor even just the washing away of sin, of which Jesus had no need.

Our God, the one in the business of revealing himself, calls people made in his Image to enter into covenant with him; the covenant in which we receive his blessing and mercy in exchange for our trusting him as our Lord, and repenting when we live as though we’re lord of our own lives.

Jesus had no sins for which to be forgiven. But, as he responded to John’s objection, his baptism is necessary, not for Jesus’ sake, but for ours – to fulfill all righteousness, as he shares our humanity.

As Jesus rises from the waters, he is revealed as God’s Son, as the perfect Son of Man, the one who succeeds in keeping God’s Law where all others have failed, the one who death cannot hold, and whose destruction of the gates of death opens the path of life; and he invites us not to a mere symbolic bath, but to enter into covenant with him, to enter into covenant with the God who, from the beginning, saves through water.

In baptism we are buried with Christ and raised to share in his resurrected life; in baptism the bonds that hold us to the fallen world are cut free and we are given a fresh start – just as with Noah, and Moses, and Joshua.

But, it isn’t magic. It’s a covenant. And covenants, like any relationship, have expectations. Blessing and mercy – boundless, unending mercy from Christ’s sacrifice of himself – offered in exchange for our trust and loyalty – a trust that knows that, when we’ve broken that loyalty, we need only to ask for forgiveness to receive his grace.

Christ’s baptism, paving the way for our baptism, joins us to God’s covenant people, the Church, the Body of Christ.

…And, maybe, in the years since your baptism, you, like the people of Israel, have lost that trust, or at times forgotten that God is to be Lord in your life. The good news, though, is that God is unchanging – he’s the same yesterday, today, and forever – and even if we let down our end of the deal, even if we forgot our promises made at baptism, even if our parents or godparents broke their promises made on our behalf, God is still keeping his: he’s standing, arms wide open, waiting to receive back the one who turns to him for mercy.

God saves through water. You’ve been washed, made a new creation in Jesus. God stands ready to keep his end of the bargain, to forgive and bless and call you a son or daughter of his kingdom – all that’s left is for us to really, truly, confess our sins, and live for our Lord.

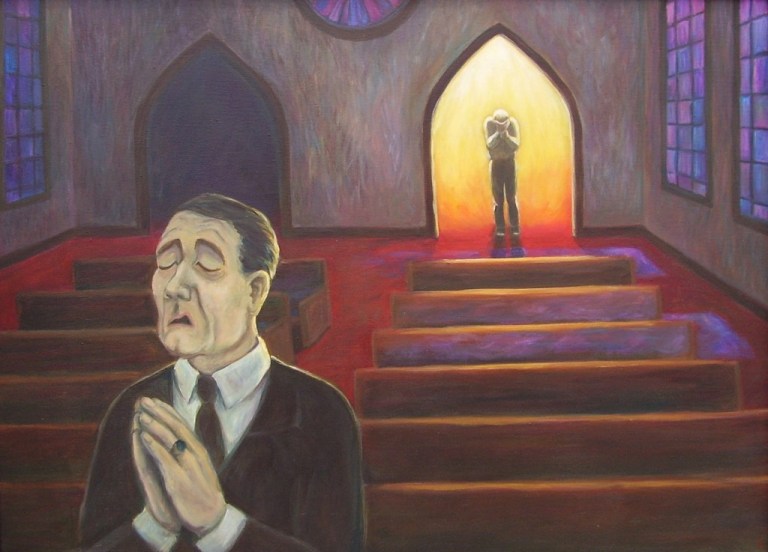

Cover image: Baptism of Christ by Daniel Bonnell